The Power of Expectations: How Price, Context, and Presentation Influence the Value We Perceive

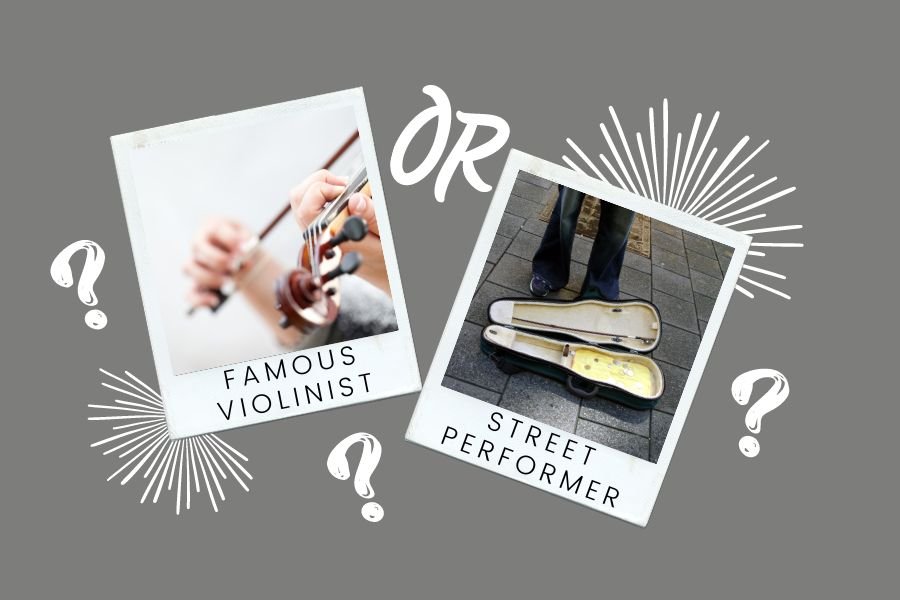

In 2007, the Washington Post conducted an experiment with world-famous violinist Joshua Bell. The musician, who made his Carnegie Hall debut at the age of 17 and has played his Stradivarius violin with many of the world's most famous orchestras and conductors, would play on a new stage—the L'Enfant Plaza metro station in Washington, DC.

Yep, he was a busker.

The experiment was to see if people would recognize a world-class musician when they weren't expecting one. Would people respond differently than if they had paid for expensive tickets to hear him in a fancy concert hall?

The answer was yes. Very few people even took notice of Bell and his Stradivarius. Only a handful of people put money in the case and even fewer listened for more than a minute.

People who paid over $100 for tickets at a standing room event in a concert hall gave him a standing ovation while people passing him in the metro station barely took notice.

This story shows the power of expectations in shaping our perceptions of quality. When you expect something to be amazing, you are more likely to think that it is.

In this experiment, the quality of the music didn’t change—only the setting and the expectations and prior knowledge of the audience.

So how does a person know what expectations to have?

In this situation, the environment was clearly one factor. Nobody expects the most amazing musicians in the world to be playing in a subway.

But it turns out that price can also influence the expectations that a person forms.

In the book Predictably Irrational, author and behavioral economics researcher Dan Ariely shows how we place higher expectations on things that cost more.

Price affects perceived value. The higher the price, the more value we think it has.

Most of us are familiar with the placebo effect—the idea that the benefits of a certain drug or procedure cannot be attributed to the placebo itself and therefore must be the result of the patient’s belief that the treatment works.

Ariely and fellow researchers did studies and experiments showing that the placebo effect is enhanced when people pay more for something, or at least believe that the item costs more. For example, a drug that cost 50 cents per pill was perceived to be more effective than one that cost one cent per pill.

This is, in fact, why brand-name drugs can be sold at a much higher cost than generics.

It is certainly true that some items made by well-known brands can be of higher quality and that the higher cost can be attributed to better (more expensive) materials.

But more often than not, expectations are at play.

In fact, it is often hard for people to correctly identify what they are getting when conducting blind taste tests. Check out this person’s mac and cheese experiment where he tried to identify which was which and often got it wrong. To top it off, his favorite ended up being the Walmart store brand mac and cheese.

You may not agree with the results (or find boxed mac and cheese worth eating at all), but it does show just how subjective our evaluations of quality can be.

So what does all this have to do with personal finance?

Primarily, that our expectations related to price lead us to purchase more expensive things simply due to the value we think we will get. Our expectations could be costing us money.

So what do you do about this?

Well, the biggest thing you can do is be aware of the effect that price has on your expectations and the value you perceive. Knowing that this is happening might make you stop and think.

Let’s say that you’re comparing two options for something you want to buy. If you find that you are leaning toward the more expensive option, you might pause and consider whether that option actually provides more value. Look for the evidence. It might be true that the more expensive item provides more value, but it might not.

For example, most of us automatically think that Whole Foods would be of higher quality than what you buy at Aldi. But have you ever done a blind taste test? Or are you just assuming? Would you notice or even pay attention if someone served you Aldi brand spaghetti sauce versus Whole Foods brand?

Now maybe you are someone who really does notice a difference between a name brand and a store brand or generic. What are you supposed to do?

One option is to just keep buying the more expensive version. Even doctors sometimes prescribe or recommend the name brand drugs because a patient perceives that it works better. And that kind of makes sense—the doctor wants you to get results, and if you get results from a placebo and there are no negative consequences, then why not?

(Though this does bring up some interesting ethical considerations around what risks or negative consequences we should accept in order to get the benefits of a placebo.)

But if money is limited, another option might be to work on changing your expectations. You can attempt to transform yourself from a person who believes the more expensive version is better to a person who believes the cost doesn’t impact effectiveness.

This isn’t easy, but it can be done. Try reading studies comparing name brand versus generics. Do your own blind taste tests or experiments. Repeat to yourself every day that your Kirkland Aller-Tec from Costco works just as well as the Zyrtec. Eventually, you’ll start to believe it.

And if you’re trying to save money, but you are worried that your friends will judge you for serving food from Aldi at the summer BBQ, here’s another tip:

Buy the cheap stuff and serve it in a fancy container.

Because it turns out that how you serve something can influence expectations just like when you listen to Joshua Bell play in a concert hall versus a metro station.